Krazy Kat

From Hey Kids Comics

| Krazy Kat | |

|---|---|

|

220px Ignatz hurls a brick at Krazy Kat, who misinterprets it as an expression of love. | |

| Author(s) | George Herriman |

| Launch date | October 28, 1913 |

| End date | June 25, 1944 |

| Syndicate(s) | King Features Syndicate |

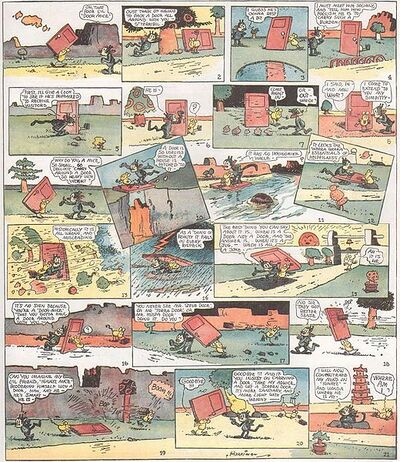

Krazy Kat is an American newspaper comic strip by cartoonist George Herriman (1880–1944), which ran from 1913 to 1944. It first appeared in the New York Evening Journal, whose owner, William Randolph Hearst, was a major booster for the strip throughout its run. The characters had been introduced previously in a side strip with Herriman's earlier creation, The Dingbat Family.[1] The phrase "Krazy Kat" originated there, said by the mouse by way of describing the cat. Set in a dreamlike portrayal of Herriman's vacation home of Coconino County, Arizona, Krazy Kat's mixture of offbeat surrealism, innocent playfulness and poetic, idiosyncratic language has made it a favorite of comics aficionados and art critics for more than 80 years.[2][3][4]

The strip focuses on the curious love triangle between its title character, a guileless, carefree, simple-minded cat of indeterminate gender (referred to as both "he" and "she"); the obsessive antagonist Ignatz Mouse; and the protective police dog, Offissa Bull Pupp. Krazy nurses an unrequited love for the mouse. However, Ignatz despises Krazy and constantly schemes to throw bricks at Krazy's head, which Krazy interprets as a sign of affection, uttering grateful replies such as "Li'l dollink, allus f'etful". Offissa Pupp, as Coconino County's administrator of law and order, makes it his unwavering mission to interfere with Ignatz's brick-tossing plans and lock the mouse in the county jail.

Despite the slapstick simplicity of the general premise, the detailed characterization, combined with Herriman's visual and verbal creativity, made Krazy Kat one of the first comics to be widely praised by intellectuals and treated as "serious" art.[2] Art critic Gilbert Seldes wrote a lengthy panegyric to the strip in 1924, calling it "the most amusing and fantastic and satisfactory work of art produced in America today."[5] Poet E. E. Cummings, another Herriman admirer, wrote the introduction to the first collection of the strip in book form. Though Krazy Kat was only a modest success during its initial run, in more recent years, many modern cartoonists have cited the strip as a major influence.

Overview[edit | edit source]

Krazy Kat takes place in a heavily stylized version of Coconino County, Arizona, with Herriman filling the page with caricatured flora and fauna, and rock formation landscapes typical of the Painted Desert.[6] These backgrounds tend to change dramatically between panels, even while the characters remain stationary. While the local geography is fluid, certain sites were stable—and featured so often in the strip as to become iconic. These latter included Offissa Pupp's jailhouse and Kolin Kelly's brickyard. A Southwestern visual style is evident throughout, with clay-shingled rooftops, trees planted in pots with designs imitating Navajo art, along with references to Mexican-American culture. The strip also occasionally features incongruous trappings borrowed from the stage, with curtains, backdrops, theatrical placards, and sometimes even floor lights framing the panel borders.

The descriptive passages mix whimsical, often alliterative language with phonetically-spelled dialogue and a strong poetic sensibility ("Agathla, centuries aslumber, shivers in its sleep with splenetic splendor, and spreads abroad a seismic spasm with the supreme suavity of a vagabond volcano.").[7] Herriman was also fond of experimenting with unconventional page layouts in his Sunday strips, including panels of various shapes and sizes, arranged in whatever fashion he thought would best tell the story.

Though the basic concept of the strip is simple, Herriman always found ways to tweak the formula. Ignatz's plans to surreptitiously lob a brick at Krazy's head sometimes succeed; other times Offissa Pupp outsmarts Ignatz and imprisons him. The interventions of Coconino County's other anthropomorphic animal residents, and even forces of nature, occasionally change the dynamic in unexpected ways. Other strips have Krazy's imbecilic or gnomic pronouncements irritating the mouse so much that he goes to seek out a brick in the final panel. Even self-referential humor is evident — in one strip, Offissa Pupp, having arrested Ignatz, berates Herriman for not having finished drawing the jailhouse.[8]

Public reaction at the time was mixed; many were puzzled by its iconoclastic refusal to conform to linear comic strip conventions and straightforward gags. But publishing magnate William Randolph Hearst loved Krazy Kat, and it continued to appear in his papers throughout its run, sometimes only by his direct order.[9]

Cast of characters[edit | edit source]

Krazy Kat[edit | edit source]

Simple-minded, curious, mindlessly happy and perpetually innocent, the strip's title character drifts through life in Coconino County without a care. Krazy's dialogue is a highly stylized argot ("A fowl konspirissy – is it pussible?")[10] phonetically evoking a mixture of English, French, Spanish, Yiddish and other dialects, often identified as George Herriman's own native New Orleans dialect, Yat.[3] Often singing and dancing to express the Kat's eternal joy, Krazy is hopelessly in love with Ignatz and thinks that the mouse's brick-tossing is his way of returning that love. Krazy is also completely unaware of the bitter rivalry between Ignatz and Officer Pupp and mistakes the dog's frequent imprisonment of the mouse for an innocent game of tag ("Ever times I see them two playing games togedda, Ignatz seems to be It").[11] On those occasions when Ignatz is caught before he can launch his brick, Krazy is left pining for the "l'il ainjil" and wonders where the beloved mouse has gone.

Krazy's own gender is never made clear and appears to be fluid, varying from strip to strip. Most authors post-Herriman (beginning with Cummings) have mistakenly referred to Krazy only as female,[12] but Krazy's creator was more ambiguous and even published several strips poking fun at this uncertainty.[13][14] When filmmaker Frank Capra, a fan of the strip, asked Herriman to straightforwardly define the character's sex, the cartoonist admitted that Krazy was "something like a sprite, an elf. They have no sex. So that Kat can't be a he or a she. The Kat's a spirit—a pixie—free to butt into anything."[15] Most characters inside the strip use "he" and "him" to refer to Krazy, likely as a gender-neutral "he".

Ignatz Mouse[edit | edit source]

Ignatz is driven to distraction by Krazy's naïveté, and he throws bricks at Krazy Kat's head. To shield his plans from Offissa Pupp, Ignatz hides his bricks, disguises himself, or enlists the aid of willing Coconino County denizens (without making his intentions clear). Easing Ignatz's task is Krazy Kat's willingness to meet him anywhere at any appointed time, eager to receive a token of affection in the form of a brick to the head. Ignatz is married with three children, though they are rarely seen.

Ironically, although Ignatz seems to generally dislike Krazy, one strip shows his ancestor, Mark Antony Mouse, fall in love with Krazy's ancestor, an Egyptian cat princess (calling her his "Star of the Nile"), and pay a sculptor to carve a brick with a love message. When he throws it at her, he is arrested, but she announces her love for him, and from that day on, he throws bricks at her to show his love for her (which would explain why Krazy believes that Ignatz throwing bricks is a sign of love). In another strip, Krazy kisses a sleeping Ignatz, and hearts appear above the mouse's head.

In the last five (or so) years of the strip, Ignatz's dislike for Krazy was noticeably downplayed. While earlier, one got the sense of his taking advantage of Krazy's willingness to be "bricked", now one gets the sense of Ignatz and Krazy as chummy co-conspirators against Pupp, with Ignatz at times quite aware of the positive way Krazy interprets his missiles.

Offissa Pupp[edit | edit source]

"Limb of Law and Arm of Order", Offissa Bull Pupp always tries—sometimes successfully—to thwart Ignatz's designs to pelt bricks at Krazy Kat. Offissa Pupp and Ignatz often try to get the better of each other even when Krazy is not directly involved, as they both enjoy seeing the other played for a fool.

Secondary characters[edit | edit source]

Beyond these three, Coconino County is populated with an assortment of incidental, recurring characters.

- Kolin Kelly: a dog; a brickmaker by trade who bakes his wares in a kiln. Often Ignatz's source for projectiles, although he distrusts the mouse.

- Mrs. Kwakk Wakk: a duck in a pillbox hat, a scold and busybody who frequently notices Ignatz in the course of his plotting and informs Offissa Pupp. She is a social climber, attempting in one strip continuity to replace Pupp as police chief.

- Joe stork: the "purveyor of progeny to prince & proletarian",[16] often makes unwanted baby deliveries to various characters. (In one strip, Ignatz tries to trick him into dropping a brick onto Krazy's head from above).

Other characters who make semi-frequent appearances are:

- Walter Cephus Austrige: a nondescript Ostrich

- Bum Bill Bee: a transient, bearded insect

- Don Kiyote: a dignified and aristocratic Mexican coyote

- Mock Duck: a clairvoyant fowl of Chinese descent who resembles a coolie and operates a cleaning establishment.

- Gooseberry Sprig: the Duck Duke, who briefly starred in his own strip before Krazy Kat was created.

- Also: Krazy's cousins Krazy Katbird and Krazy Katfish. Ignatz also has relations; his family of look-alike mice includes his wife, Magnolia and a trio of equally unruly sons named Milton, Marshall and Irving.

History[edit | edit source]

Krazy Kat evolved from an earlier comic strip of Herriman's, The Dingbat Family, which started in 1910 and was later renamed The Family Upstairs. This comic chronicled the Dingbats' attempts to avoid the mischief of the mysterious unseen family living in the apartment above theirs and to unmask that family. Herriman would complete the cartoons about the Dingbats, and finding himself with time left over in his 8-hour work day, filled the bottom of the strip with slapstick drawings of the upstairs family's mouse preying upon the Dingbats' cat.[17]

This "basement strip" grew into something much larger than the original cartoon. It became a daily comic strip with a title (running vertically down the side of the page) on October 28, 1913 and a black and white full-page Sunday cartoon on April 23, 1916. Due to the objections of editors, who didn't think it was suitable for the comics sections, Krazy Kat originally appeared in the Hearst papers' art and drama sections.[18] Hearst himself, however, enjoyed the strip so much that he gave Herriman a lifetime contract and guaranteed the cartoonist complete creative freedom.

Despite its low popularity among the general public, Krazy Kat gained a wide following among intellectuals. In 1922, a jazz ballet based on the comic was produced and scored by John Alden Carpenter; though the performance played to sold-out crowds on two nights[19] and was given positive reviews in The New York Times and The New Republic,[20] it failed to boost the strip's popularity as Hearst had hoped. In addition to Seldes and Cummings, contemporary admirers of Krazy Kat included Willem de Kooning, H. L. Mencken, and Jack Kerouac.[4] More recent scholars and authors have seen the strip as reflecting the Dada movement[21] and prefiguring postmodernism.[3][22]

Beginning in 1935, Krazy Kat's Sunday edition was published in full color. Though the number of newspapers carrying it dwindled in its last decade, Herriman continued to draw Krazy Kat—creating roughly 3,000 cartoons—until his death in April 1944 (the final page was published exactly two months later, on June 25). Hearst promptly canceled the strip after the artist died, because, contrary to the common practice of the time, he did not want to see a new cartoonist take over.[23]

Animated adaptations[edit | edit source]

The comic strip was animated several times (see filmography below). The earliest Krazy Kat shorts were produced by Hearst in 1916. They were produced under Hearst-Vitagraph News Pictorial and later the International Film Service (IFS), though Herriman was not involved. In 1920, after a two-year hiatus, the John R. Bray studio began producing a second series of Krazy Kat shorts.[24] These cartoons hewed close to the comic strips, including Ignatz, Pupp and other standard supporting characters. Krazy's ambiguous gender and feelings for Ignatz were usually preserved; bricks were occasionally thrown.

In 1925, animation pioneer Bill Nolan decided to bring Krazy to the screen again. Nolan intended to produce the series under Associated Animators, but when it dissolved, he sought distribution from Margaret J. Winkler. Unlike earlier adaptations, Nolan did not base his shorts on the characters and setting of the Herriman comic strip. Instead, the feline in Nolan's cartoons was a male cat whose design and personality both reflected Felix the Cat. This is probably due to the fact that Nolan himself was a former employee of the Pat Sullivan studio.[25] Other Herriman characters appeared in the Nolan cartoons at first, though similarly altered: Kwakk Wakk was at times Krazy's paramour,[26] with Ignatz often the bully trying to break up the romance.[27] Over time, Nolan's influence waned and new directors, Ben Harrison and Manny Gould, took over the series. By late 1927, they were solely in charge.

Winkler's husband, Charles B. Mintz, slowly began assuming control of the operation. Mintz and his studio began producing the cartoons in sound beginning with 1929's Ratskin. In 1930, he moved the staff to California and ultimately changed the design of Krazy Kat. The new character bore even less resemblance to the one in the newspapers. Mintz's Krazy Kat was, like many other early 1930s cartoon characters, imitative of Mickey Mouse, and usually engaged in slapstick comic adventures with his look-alike girlfriend and loyal pet dog.[28] In 1936, animator Isadore Klein, with the blessing of Mintz, set to work creating the short, Lil' Ainjil, the only Mintz work that was intended to reflect Herriman's comic strip. However, Klein was "terribly disappointed" with the resulting cartoon, and the Mickey-derivative Krazy returned.[29] In 1939, Mintz became indebted to his distributor, Columbia Pictures, and subsequently sold his studio to them.[30] Under the name Screen Gems, the studio produced only one more Krazy Kat cartoon, The Mouse Exterminator in 1940.[31]

King Features produced 50 Krazy Kat cartoons from 1962–1964, most of which were created at Gene Deitch's Rembrandt Films in Prague, Czechoslovakia (now the Czech Republic), whilst the rest were produced by Artransa Film Studios in Sydney, Australia. The cartoons were initially televised interspersed with Beetle Bailey (some of which were also produced by Artransa) and Snuffy Smith cartoons to form a half-hour TV show. These cartoons helped to introduce Herriman's cat to the baby boom generation. The King Features shorts were made for television and have a closer connection to the comic strip; the backgrounds are drawn in a similar style, and Ignatz and Offissa Pupp are both present. This incarnation of Krazy was made female; Penny Phillips voiced Krazy while Paul Frees voiced Ignatz and Offissa Pupp. Jay Livingston and Ray Evans did the music for most of the episodes.[24] Most of the episodes are available on DVD.

A "Kounterfeit Krazy"[edit | edit source]

In 1951, Dell Publishing revived the characters for a run of comic books. All five issues were drawn by cartoonist John Stanley, best known for his Little Lulu comic books.[32] While the general plot premise is reminiscent of Herriman's strip, the look and feel are entirely different: firmly in the visual and written style of 1950s "funny animal" strips for children. Krazy is male in this version of the strip. This "Krazy Kat" also made several one-shot appearances in Dell's Four Color Comics series, from 1953 through 1956 (#454, 504, 548, 619, 696,)[33] and was reprinted in some Gold Key and Page Comics over the next decade.

Chronology of formats[edit | edit source]

The strip went through several format changes during its run, each of which impacted the artwork and the narratives that the form of the strip could accommodate. What follows are the landmarks, which can also help to date the era of a given strip.

- July 26, 1910: First "beaning" of Kat by Mouse at bottom of The Dingbat Family. Strip is not sectioned off, but a detail at the bottom of the panels. Strip as a whole tended to run 4 inches × 13 inches. Soon the Kat and Mouse were a five-panel 1½ inch strip at the bottom of the cartoon.[34]

- 1911: First brief run of Krazy and I. Mouse standalone strips (probably as a replacement to The Family Upstairs). Also, the characters briefly take over the strip for a couple of periods in 1912 (at least once, while the Dingbats are "on holiday" in July 1912.)

- October 28, 1913. Krazy Kat debuts as a five-panel daily vertical strip which runs down the side of a full comics page. This remains its daily format until sometime in 1920.[35]

- April 23, 1916: First black & white full page Sunday strip.

- March 4, 1920 – October 30, 1920: The "Panoramic Dailies" period, where Herriman is allowed to experiment wildly in an unbroken daily horizontal 3 × 13 inch space.

- November 1920 on: Herriman is constrained to a more conventional daily horizontal format containing three equal split sections, with the center section further split in two. This allows the strip to be run full page, half page or a third of a page, according to editorial whim. From September 13 to October 15, 1921, Herriman regains some control (no split center section) and resumes the previous years' format experiments.

- January 7, 1922 – March 11, 1922: In the New York Journal, 10 weeks of Saturday full-page color strips, in addition to the ongoing Sunday full page black-and-white strips. (In other words, two original full-page strips every week). This is then canceled due to its lack of noticeable commercial success, compared to the new Saturday color sections in out-of-town Hearst papers which contained no Krazy Kat.[36]

- August 1925 to September 1929: Sundays are confined to 3-row, split-middle-line format allowing some papers to reduce cartoon's size and reformat into two daily-sized rows.[37]

- Summer 1934: Full page Sunday strips cease entirely, for roughly a year.

- June 1, 1935: Full page Sunday strips resume, now in color, until Herriman's death.

- December 11, 1938: "Optional" horizontal panel begins running on bottom of Sunday strips, as placeholder for potential advertising.

- June 25, 1944: Final Sunday strip published.

Legacy[edit | edit source]

In 1999, Krazy Kat was rated #1 in a Comics Journal list of the best American comics of the 20th century; the list included both comic books and comic strips.[38] In 1995, the strip was one of 20 included in the Comic Strip Classics series of commemorative U.S. postage stamps.

While Chuck Jones' Wile E. Coyote and Road Runner shorts, set in a similar visual pastiche of the American Southwest, are among the most famous cartoons to draw upon Herriman's work,[22] Krazy Kat has continued to inspire artists and cartoonists to the present day. Patrick McDonnell, creator of the current strip Mutts and co-author of Krazy Kat: The Comic Art of George Herriman, cites it as his "foremost influence."[39] Bill Watterson of Calvin and Hobbes fame named Krazy Kat among his three major influences (along with Peanuts and Pogo).[40] Watterson would revive Herriman's practice of employing varied, unpredictable panel layouts in his Sunday strips. Charles M. Schulz[41] and Will Eisner[42] both said that they were drawn towards cartooning partly because of the impact Krazy Kat made on them in their formative years. Bobby London's Dirty Duck was styled after Krazy Kat.

In the 1980s, Bob Laughlin created comic-book characters "Kitz 'n' Katz," who appeared in a six-issue run partly published by Eclipse Comics.[43][44] The artwork and stories were reminiscent of Krazy Kat, and the title characters sometimes referred to an "Uncle Krazy" whom we never saw.

Jules Feiffer,[45] Philip Guston,[45] and Hunt Emerson[46] have all had Krazy Kat's imprint recognized in their work. Larry Gonick's comic strip Kokopelli & Company is set in "Kokonino County", an homage to Herriman's exotic locale. Chris Ware admires the strip, and his frequent publisher, Fantagraphics, is currently reissuing its entire run in volumes designed by Ware (which also include reproduction of Herriman miscellanea, some of it donated by Ware). In the 1980s, Sam Hurt's syndicated strip Eyebeam shows a clear Herriman influence, particularly in its continually morphing backgrounds. Among non-cartoonists, Jay Cantor's 1987 novel Krazy Kat uses Herriman's characters to analyze humanity's reaction to nuclear weapons, while Michael Stipe of the rock band R.E.M. has a tattoo of Ignatz and Krazy.[47] In one Garfield comic strip, where it shows the Garfield logo, you can see Ignatz throwing a brick at Garfield. Also, in the Garfield TV special Garfield: His 9 Lives, Garfield plays a stunt double for Krazy Kat. In one 1989 Bloom County strip by Berke Breathed, Krazy and Ignatz can be seen watching Binkley, Oliver, and Opus float through a Herriman-esque landscape.

Reprints and compilations[edit | edit source]

For many decades, Herriman's strip was only sporadically available. The first Krazy Kat collection, published by Henry Holt and Company in 1946, just two years after Herriman's death, gathered 200 selected strips.[48] In Europe, the cartoons were first reprinted in 1965 by the Italian magazine Linus, and appeared in the pages of the French monthly Charlie Mensuel starting in 1970.[49] In 1969, Grosset & Dunlap produced a single hardcover collection of selected episodes and sequences spanning the entire length of the strip's run. The Netherlands' Real Free Press published five issues of "Krazy Kat Komix" in 1974-1976, containing a few hundred strips apiece; each of the issues' covers was designed by Joost Swarte. However, owing to the difficulty of tracking down high-quality copies of the original newspapers, no plans for a comprehensive collection of Krazy Kat strips surfaced until the 1980s.

All of the Sunday strips from 1916 to 1924 were reprinted by Eclipse Comics in cooperation with Turtle Island Press. The intent was to eventually reprint every Sunday Krazy Kat, but this planned series was aborted when Eclipse ceased business in 1992. Beginning in 2002, Fantagraphics resumed reprinting Sunday Krazy Kats where Eclipse left off; in 2008, their tenth release completed the run with 1944. Fantagraphics' future plans involve reissuing in the same format the strips previously printed in Eclipse's now out-of-print volumes.[50] Both the Eclipse and Fantagraphics reprints include additional rarities such as older George Herriman cartoons predating Krazy Kat.

Kitchen Sink Press, in association with Remco Worldservice Books, reprinted two volumes of color Sunday strips dating from 1935 to 1937; but like Eclipse, they collapsed before they could continue the series.[51]

The daily strips for 1921 to 1923 were reprinted by Pacific Comics Club. The 1922 and 1923 books skipped a small number of strips, which have now been reprinted by Comics Revue. Comics Revue has also published all of the daily strips from September 8, 1930 through December 31, 1934. Fantagraphics come out with a one-shot reprint of daily strips from 1910s and 1920s in 2007, and plans a more complete reprinting of the daily strip in the future.

Scattered Sundays and dailies have appeared in several collections, including the Grosset & Dunlap book reprinted by Nostalgia Press, but the most readily available sampling of Sundays and dailies from throughout the strip's run is Krazy Kat: The Comic Art of George Herriman, published by Harry N. Abrams, Inc. in 1986.[51][52] It includes a detailed biography of Herriman and was, for a long time, the only in-print book to republish Krazy Kat strips from after 1940. Although it contains over 200 strips, including many color Sundays, it is light on material from 1923 to 1937.

Henry Holt & Co.[edit | edit source]

- Krazy Kat (1946) Introduction by e.e. cummings. Hardcover B&W compilation of daily and Sunday strips, concentrating on 1930–1944.

Grosset & Dunlap/Nostalgia Press/Madison Square Press[edit | edit source]

- Krazy Kat: A Classic from the Golden Age of Comics (1969, 1975) An entirely different compilation of dailies and Sundays, with examples from the entire run of the strip—including 23 "Dingbat Family" bottom strips. Reprints the e.e. cummings introduction from the Henry Holt volume. 8 pages in full color; some later editions have daily strips reproduced in blue ink. ISBN 0-448-11945-5 (hardcover), ISBN 0-448-11951-X (paperback)

Street Enterprises (Menomonee Falls)[edit | edit source]

- (George Herriman's) Krazy Kat Vol. 1, No. 1 (March 1973) 32-page newsprint magazine reprinting 60 daily strips from July 3–October 28, 1933. (Inside cover claims inaccurately that they are from 1935.)

Real Free Press[edit | edit source]

- Krazy Kat Komix, Nos. 1-5 (1974–1976) Joost Swarte, ed. The 5-issue magazine also features other Herriman strips.

Hyperion Press[edit | edit source]

- The Family Upstairs: Introducing Krazy Kat: The Complete Strip, 1910–1912 (1977, 1992) Introduction by Bill Blackbeard. ISBN 0-88355-643-X (hardcover), ISBN 0-88355-642-1 (softcover)

Harry N. Abrams[edit | edit source]

- Krazy Kat: The Comic Art of George Herriman (1986) Patrick McDonnell, Karen O'Connell, eds. Various strips in B&W and color, mostly from original art, including some watercolor paintings. ISBN 0-8109-8152-1 (hardcover), ISBN 0-8109-9185-3 (softcover)

Morning Star Publications[edit | edit source]

- Coconino Chronicle (1988) Alec Finlay, ed. 130 strips from 1927–1928.

Eclipse Comics[edit | edit source]

"Krazy and Ignatz: The Komplete Kat Komics" (series), Bill Blackbeard, ed. Each of these volumes reprints a year of Sunday strips.

- Vol 1: Krazy & Ignatz (1988) 1916 strips. ISBN 0-913035-49-1

- Vol 2: The Other Side To the Shore Of Here (1989) 1917 strips. ISBN 0-913035-74-2

- Vol 3: The Limbo of Useless Unconsciousness (1989) 1918 strips. ISBN 0-913035-76-9

- Vol 4: Howling Among the Halls of Night (1989) 1919 strips. ISBN 1-56060-019-5

- Vol 5: Pilgrims on the Road to Nowhere (1990) 1920 strips. ISBN 1-56060-023-3

- Vol 6: Sure As Moons is Cheeses (1990) 1921 strips. ISBN 1-56060-034-9

- Vol 7: A Katnip Kantata in the Key of K (1991) 1922 strips, including 10 color Saturday strips. ISBN 1-56060-063-2

- Vol 8: Inna Yott On the Muddy Geranium (1991) 1923 strips. ISBN 1-56060-066-7

- Vol 9: Shed a Soft Mongolian Tear (1992) 1924 strips. ISBN 1-56060-102-7

- Vol 10: Honeysuckil Love is Doubly Swit (unpublished) 1925 strips. ISBN 1-56060-203-1

Kitchen Sink Press[edit | edit source]

"The Komplete Kolor Krazy Kat" (series). Each volume reprinted two years of Sundays. (The publisher dissolved before the series' aim of completeness could be achieved.)

- Vol 1: 1935–1936 (1990) Rick Marshall, Bill Watterson, contributors. ISBN 0-924359-06-4

- Vol 2: 1936–1937 (1991) Rick Marshall, ed. ISBN 0-924359-07-2

Stinging Monkey/BookSurge[edit | edit source]

- Krazy & Ignatz, The Dailies. Vol 1: 1918–1919 (2001, 2003) Gregory Fink, ed., introduction by Bill Blackbeard. (Stinging Monkey edition in large format, ISBN 978-0-9688676-0-0. BookSurge reprint in smaller 7.9 × 6 inch format, ISBN 1-59109-975-7, ISBN 978-1-59109-975-8)

Pacific Comics[edit | edit source]

"All the Daily Strips...." (series) 6¼ x 6¼ inch format.

- Krazy Kat vol 1: 1921 (2003)

- Krazy Kat vol 2: 1922 (2004)

- Krazy Kat Vol 3: 1923 (2005)

"Presents Krazy and Ignatz" (series) Four 3¼ x 4 inch volumes reproducing the 1921 strips in miniature.

Fantagraphics Books[edit | edit source]

(Picking up where Eclipse left off, each of the following volumes reprints 2 years of Sundays. Bill Blackbeard, series editor. Chris Ware, designer. The first five volumes are in B&W, as originally printed.)

- Krazy & Ignatz in "There Is A Heppy Lend Furfur A-Waay": 1925–1926 (2002) ISBN 1-56097-386-2

- Krazy & Ignatz in "Love Letters In Ancient Brick": 1927–1928 (2002) ISBN 1-56097-507-5

- Krazy & Ignatz in "A Mice, A Brick, A Lovely Night": 1929–1930 (2003) ISBN 1-56097-529-6

- Krazy & Ignatz in "A Kat Alilt with Song": 1931–1932 (2004) ISBN 1-56097-594-6

- Krazy & Ignatz in "Necromancy by the Blue Bean Bush": 1933–1934 (2005) ISBN 1-56097-620-9

- Krazy & Ignatz: The Complete Sunday Strips: 1925–1934 (Collects the five paperback volumes 1925–1934 in a single hardcover volume. Only 1000 copies printed, only available by direct order from the publisher.) ISBN 1-56097-522-9

(The following volumes, through 1944, are in color, reflecting the shift to color in the Sunday newspaper version.)

- Krazy & Ignatz in "A Wild Warmth of Chromatic Gravy": 1935–1936 (2005) ISBN 1-56097-690-X, 2005

- Krazy & Ignatz in "Shifting Sands Dusts its Cheeks in Powdered Beauty": 1937–1938 (2006) ISBN 1-56097-734-5

- Krazy & Ignatz in "A Brick Stuffed with Moom-bins": 1939–1940 (2007) ISBN 1-56097-789-2

- Krazy & Ignatz in "A Ragout of Raspberries": 1941–1942 (2007) ISBN 1-56097-887-2

- Krazy & Ignatz in "He Nods in Quiescent Siesta": 1943–1944 (2008) ISBN 1-56097-932-1

- Krazy & Ignatz: The Complete Sunday Strips: 1935–1944 (Collects the five paperback volumes 1935–1944 in a single hardcover volume. Only 1000 copies printed, only available by direct order from the publisher.)

- Krazy & Ignatz: The Kat Who Walked in Beauty (2007) 11" × 15" horizontal hardcover; reprints dailies from 1911–12, 1914, 9 months of large-format dailies from 1920 with an additional month from late 1921, and 1922 pantomime ballet artwork. ISBN 1-56097-854-6

- Krazy & Ignatz in "Love in a Kestle or Love in a Hut": 1916–1918 (2010) ISBN 1-60699-316-X

- Krazy & Ignatz in "A Kind, Benevolent and Amiable Brick": 1919–1921 (2011) ISBN 1-60699-364-X

- Krazy & Ignatz in "At Last My Drim of Love Has Come True": 1922-1924 (2012) ISBN 1-60699-477-8 (also includes Us Husbands)

Sunday Press Books[edit | edit source]

- Krazy Kat: A Celebration of Sundays (2010) Patrick McDonnell, Peter Maresca, eds. Various Sundays reprinted in their original size and colors. ISBN 0-9768885-8-0 (hardcover)

IDW Publishing[edit | edit source]

- George Herriman's Krazy + Ignatz in Tiger Tea (January 2010) Craig Yoe, ed. Collects the "Tiger Tea" storyline from the daily strips, May 1936-March 1937. ISBN 978-1-60010-645-3 (hardcover)

See also[edit | edit source]

- Krazy Kat filmography, a complete list of theatrical cartoons based on the comic strip.

- The Krazy Kat Klub, a Bohemian nightspot in Washington, DC during the early decades of the 20th century, named after the comic strip.

References[edit | edit source]

- Blackbeard, Bill. "A Kat of Many Kolors: Jazz pantomime and the funny papers in 1922." (1991). Printed in A Katnip Kantata in the Key of K (q.v.)

- Bloom, John. "Krazy Kat keeps kracking." United Press International, June 23, 2003.

- Crafton, Donald (1993). Before Mickey: The Animated Film, 1898–1928. University of Chicago Press. ISBN 0-226-11667-0.

- Crocker, Elisabeth. "'To He, I Am For Evva True': Krazy Kat's Indeterminate Gender." Postmodern Culture, January 1995. January 12, 2006.

- Heer, Jeet. "Cartoonists in Navajo Country." Comic Art, Summer 2006. 40–47.

- Herriman, George (1990). Pilgrims on the Road to Nowhere. Forestville: Turtle Island, Eclipse Books. ISBN 1-56060-024-1.

- Herriman, George (1991). A Katnip Kantata in the Key of K. Forestville: Turtle Island/Eclipse Books. ISBN 1-56060-064-0.

- Herriman, George (2002). Krazy & Ignatz 1925–1926: "There Is A Heppy Land, Fur, Far Awa-a-ay -". Seattle: Fantagraphics Books. ISBN 1-56097-386-2.

- Herriman, George (2003). Krazy & Ignatz 1929–1930: "A Mice, A Brick, A Lovely Night". Seattle: Fantagraphics Books. ISBN 1-56097-529-6.

- Herriman, George (2004). Krazy & Ignatz 1933–1934: "Necromancy by the Blue Bean Bush". Seattle: Fantagraphics Books. ISBN 1-56097-620-9.

- Inge, Thomas (1990). "Krazy Kat as American Dada Art" Comics as Culture, Jackson: University Press of Mississippi. ISBN 0-87805-408-1.

- Kramer, Hilton. Untitled review of Herriman art exhibition. The New York Times, January 17, 1982.

- Maltin, Leonard (1987). Of Mice and Magic: A History of American Animated Cartoons. Penguin Books. ISBN 0-452-25993-2.

- McDonnell, Patrick; O'Connell, Karen; de Havenon, Georgia Riley (1986) Krazy Kat: The Comic Art of George Herriman. New York: Harry N. Abrams, Inc. ISBN 0-8109-2313-0.

- Schwartz, Ben (2003). "Hearst, Herriman, and the Death of Nonsense." Printed in Krazy & Ignatz 1929–1930: "A Mice, A Brick, A Lovely Night." (q.v.)

- Shannon, Edward A. "'That we may mis-unda-stend each udda': The Rhetoric of Krazy Kat." Journal of Popular Culture, Fall 1995, vol. 29, issue 2.

- Tashlin, Frank. "In Coconino County". The New York Times, November 3, 1946, p. 161.

- Watterson, Bill (1995). The Calvin and Hobbes Tenth Anniversary Book. Kansas City: Andrews and McMeel. ISBN 0-8362-0438-7

Notes[edit | edit source]

- ↑ Blackbeard, Bill and Martin Williams, "The Smithsonian Collection of Newspaper Comics". pp. 59–60.

- ↑ 2.0 2.1 Kramer.

- ↑ 3.0 3.1 3.2 Shannon.

- ↑ 4.0 4.1 McDonnell/O'Connell/De Havenon 26.

- ↑ Seldes, Gilbert. "The Krazy Kat That Walks By Himself". The Seven Lively Arts. New York: Harper and Brothers, 1924, p. 231.

- ↑ Heer 41–45.

- ↑ A Mice, A Brick, A Lovely Night 71.

- ↑ Krazy Kat: The Comic Art of George Herriman 97.

- ↑ Schwartz 8–10.

- ↑ Pilgrims on the Road to Nowhere, 47.

- ↑ There is a Heppy Lend, Fur, Fur Awa-a-ay-, 62.

- ↑ Crocker.

- ↑ Necromancy By the Blue Bean Bush, 16–17.

- ↑ A Katnip Kantata in the Key of K, 71.

- ↑ Schwartz 9.

- ↑ A Mice, A Brick, A Lovely Night 67, et al.

- ↑ McDonnell/O'Connell/De Havenon 52.

- ↑ McDonnell, O'Connell and De Havenon 58.

- ↑ Blackbeard 1–3.

- ↑ McDonnell, O'Connell and De Havenon 66–67.

- ↑ Inge.

- ↑ 22.0 22.1 Bloom.

- ↑ Schwartz 9–10.

- ↑ 24.0 24.1 Crafton.

- ↑ Maltin 205–06.

- ↑ Winkler Productions: copyright synopsis for Web Feet (1927).

- ↑ Rail Rode.

- ↑ Maltin 207.

- ↑ Maltin 210–11.

- ↑ Maltin 213.

- ↑ Screen Gems, The Columbia Crow's Nest — Columbia Cartoon History.

- ↑ Young, Frank M. (August 9, 2008). "from 'Krazy Kat' #4, 1952: soup's on!". Stanley Stories. Retrieved October 7, 2011.

- ↑ "Dell Four Color Comics".[dead link]

- ↑ McDonnell/O'Connell/De Havenon 55.

- ↑ McDonnell/O'Connell/De Havenon 57.

- ↑ A Katnip Kantata in the Key of K, 1-3

- ↑ McDonnell/O'Connell/De Havenon 77.

- ↑ "Kreem of the Komics!", Detroit Metrotimes. Retrieved on January 13, 2005.

- ↑ comic masters. Retrieved on January 13, 2005. Archived March 18, 2005 at the Wayback Machine

- ↑ Watterson 17–18.

- ↑ Charles Schulz, interviewed by Rick Marschall and Gary Groth in Nemo 31, January 1992. Cited at [1] (URL retrieved January 13, 2005). Archived February 8, 2005 at the Wayback Machine

- ↑ The Onion AV Club interview with Will Eisner, September 27, 2000. Retrieved on January 13, 2005.

- ↑ Kitz 'n' Katz at Katz.us

- ↑ Kitz 'n' Katz Komiks at the Comic Book DB

- ↑ 45.0 45.1 Comics in Context #20: This Belongs in a Museum. Retrieved on January 13, 2005.

- ↑ The artsnet interview: Hunt EMERSON. Retrieved January 13, 2005.

- ↑ Rec.music.rem FAQ (#A15). Retrieved January 13, 2005.

- ↑ Tashlin.

- ↑ Exhibit catalog from the Musée de la bande dessinée in Angoulême, 1997, cited in BDM 2005–2006, by Bera, Denni and Mellot.

- ↑ There is a Heppy Lend, Fur, Fur Awa-a-ay-, 119.

- ↑ 51.0 51.1 Krazy Kat online bibliography

- ↑ The Mouse Bibliography

External links[edit | edit source]

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Krazy Kat. |

- Krazy Kat at Internet Archive (comic strips, video and audio)

- Coconino County — History, bios, strip archive, bibliography and more.

- "'Some Say it With A Brick': George Herriman's Krazy Kat" — A critical essay.

- Full video of the "Krazy Goes A-Wooing" silent animated short produced by Hearst, with some similarities to the strip.

- The Columbia Crow's Nest — Includes information on the Mintz-era cartoons bearing the Krazy Kat name.

- Ignatz Mouse — A site built around the second character of the strip. Forums, archives, etc...

- Krazy Kat Cartoons from the 1960s — A list of Krazy Kat cartoons in full-colors.

- Comic Strip Library — Archive of many strips in very high resolution.

- Bill Watterson's foreword of the book "The Komplete Kolor Krazy Kat"

| ||||||||

- All articles with dead external links

- Articles with dead external links from October 2011

- Articles with invalid date parameter in template

- Commons category template with no category set

- Commons category with page title different than on Wikidata

- American comic strips

- Comic strips started in the 1910s

- Columbia cartoons series and characters

- Comics featuring anthropomorphic characters

- Fantagraphics Books titles

- Fictional cats

- Fictional characters from Arizona

- Comics characters

- Kitchen Sink Press titles

- Androgyny

- Articles containing video clips